Three artists to know that use IA

While much of the debate around AI revolves around plagiarism and standardization, some artists are showing us that algorithms can be more than tools: they can become artistic materials in their own right. By using code and datasets as pigments and brushes, these creators question what it means to make art in the digital age.

When AI becomes an artistic material

Vera Molnár: The pioneer of algorithmic art

Decades before artificial intelligence dominated headlines, Franco-Hungarian artist Vera Molnár was already experimenting with computers. Known for her work in geometric abstraction, she applied mathematical rules to composition and allowed randomness to guide her creative process. In the 1960s, she described her experiments as “imaginary machines,” writing programs that she initially executed by hand before turning them over to actual computers.

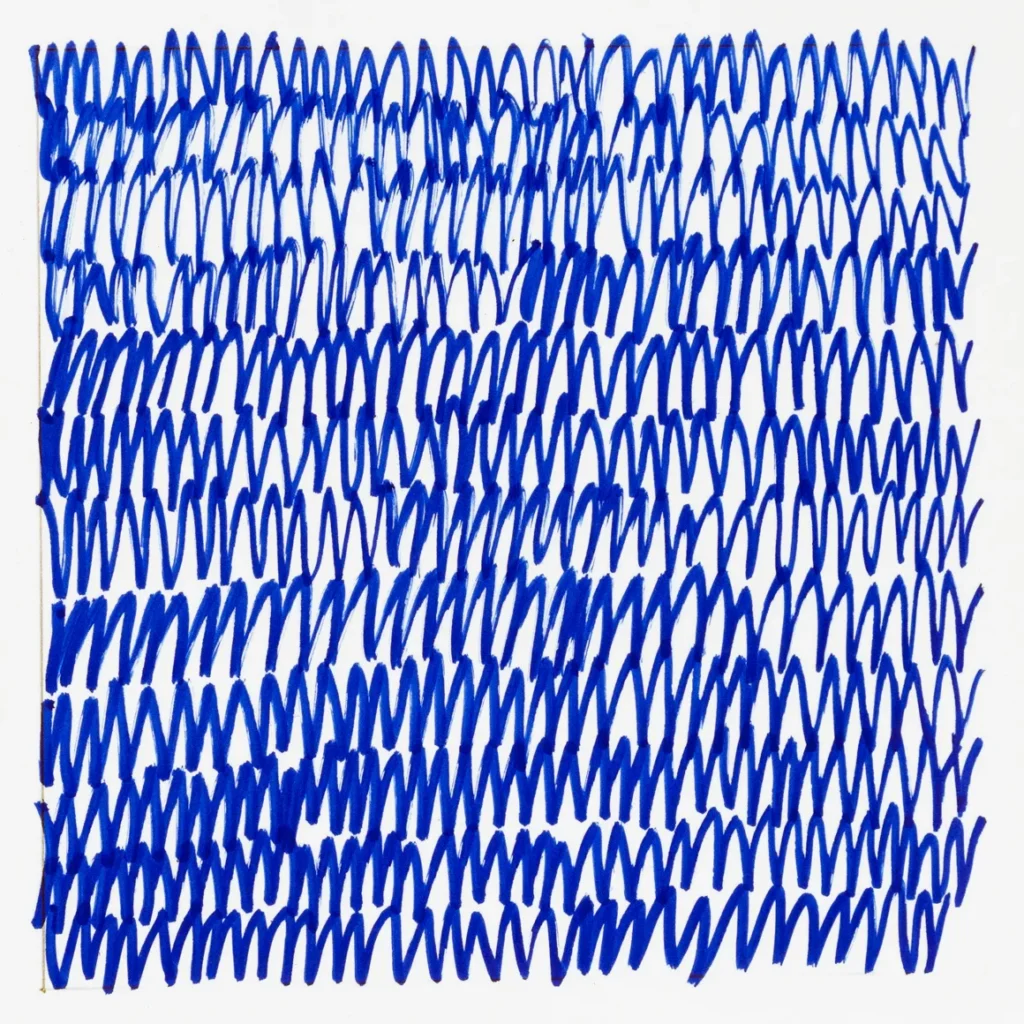

Vera Molnár never saw the computer as a gadget but as a tool for expanding creative possibilities. With her husband François, she developed Molnart in 1974, a program that generated square-based compositions to which she deliberately added a touch of imperfection—her trademark “1% of disorder.” By introducing controlled randomness, she blurred the line between order and chaos, making her work feel more human.

She later recalled how transformative it was to have a computer at home: “We would fall asleep to the sound of the plotter, like an obedient servant working tirelessly in my place.” Using this technology, Molnár experimented with lines, shapes, letters, and even tore paper in her Mont Sainte-Victoire series, a nod to Cézanne.

Since 1976, she kept detailed journals of her process. In 2022, she donated twenty-two volumes to the Centre Pompidou—digitized so she could still revisit them—even after leaving her studio in 2021 to move into care.

Serigraphy on paper

Mario Klingemann: The machine that dreams in real time

German artist Mario Klingemann is considered one of the leading figures in AI-based art. His installation Memories of Passersby I (2018) features a wooden console containing an AI “brain” and two screens that continuously display portraits of men and women. The images are not pre-recorded; they are generated in real time by a neural network trained on classic portraiture and surrealist influences.

Her works of lines, grids, and permutations demonstrate how beauty can emerge from controlled accidents. Molnár believed that computers were not rivals but liberators, freeing artists to explore possibilities that the human hand alone could not. She is now recognized as a pioneer of generative and algorithmic art, her work offering a valuable lesson for the fashion industry: algorithmic systems can inspire new approaches to patterns, prints, and modular design.

Each portrait appears, mutates, and fades away, never to be repeated in the exact same way. The result is haunting, as if the machine itself were dreaming, inventing new faces on the spot. For fashion, this type of work raises exciting questions: could shows or campaigns become living, evolving experiences, constantly refreshed by AI while guided by a human creative director?

Anna Ridler: Turning data into poetry

London-based artist and researcher Anna Ridler represents a new generation of creators who see data as their raw material. Unlike many who rely on publicly available datasets, Ridler painstakingly creates her own. This allows her to maintain control over the narratives her AI systems generate.

Her best-known work, Mosaic Virus (2018–2019), connects two seemingly distant events: the Tulip Mania of the 17th century and the rise of Bitcoin. By linking the price of Bitcoin to the appearance of tulips generated by AI, Ridler visualizes the speculative logic that drives both flowers and cryptocurrencies. As Bitcoin prices fluctuate, so too do the tulips—becoming more complex and marbled when values soar.

Her approach transforms AI into a mirror of economic and cultural forces, showing how algorithms can critique the very systems they emerge from. For fashion, Ridler’s work highlights how data—consumer trends, markets, cultural signals—can be turned not just into predictions, but into poetry.

Installation of Myriad (Tulips)

Single screen installation

Conclusion

What unites Molnár, Klingemann, and Ridler is not their reliance on technology but their ability to bend it to their vision. Each reveals invisible logics—mathematical, historical, or economic—through artistic form. Their work shows that AI, far from replacing creativity, can expand it, offering new aesthetics and new questions. For the creative industries and for fashion, their message is clear: the future lies not in machines creating instead of humans, but in humans creating with machines.